1. Introduction – the problem of “county confusion”

2. The three types of “county”

2.1 The historic counties of Britain

2.2 The “counties” of the Local Government Act 1972

2.3 The “counties” of the Lieutenancies Act 1997

3. A proposed terminology to clear the confusion

4. Concluding remarks – a fixed popular geography

1. Introduction – the problem of “county confusion”

Until recently, the historic (or traditional) Counties of Great Britain were universally used as the standard general-purpose geographical reference frame of Britain. The location of every village, town and city of Britain could be simply described by reference to one of these Counties. We literally knew where we were.

Now we live in an era of geographical confusion. The historic counties are still important cultural entities. Many people have a strong sense of identity with them. Many sporting, social and cultural activities are based upon them. They are also widely used by many as a popular geographical framework. All of them are a valid part of Royal Mail postal addresses. Yet many commercial map-makers, publishers of guide books and sections of the media have ceased to use them as a geographical reference frame. Instead attempts are made to use one or other of the two different sets of modern administrative areas both of which have been given the label “counties”, i.e.,

(i) those modern local government areas (in England and Wales) deemed “to be known as counties” by the Local Government Act 1972 (LGA 1972)

(ii) those areas (in England and Wales) within which lord-lieutenants have jurisdiction and which have been labelled “counties” for the purposes of the Lieutenancies Act 1997 (LA 1997)

In each of these Acts the word “county” is nothing more than a label for the areas so defined by the Act. These “counties” have no existence beyond the narrow confines of the Acts. The Government has consistently made this clear, e.g. on 1st April 1974, upon implementation of the LGA 1972, a Government statement said:

“The new county boundaries are solely for the purpose of defining areas of … local government. They are administrative areas, and will not alter the traditional boundaries of Counties, nor is it intended that the loyalties of people living in them will change.”

Despite this, the administrative “counties” are widely used in a popular geographical context. All three types of “county” can be encountered, often mixed up together. For example, one can listen to a radio news report which refers to an incident in “Bolton, Lancashire” (its historic county) followed by another in “Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire” (its LGA 1972 “county”). The travel news will then refer to an accident in “Gwent” (a LA 1997 “county”). The geographical confusion which results from mixing together three different reference frames is greatly exacerbated by the fact that many of the administrative “counties” share the name of a historic county but have a radically different area. In Lancashire, for example, the historic county has a much larger area than the LA 1997 “county” of “Lancashire” which itself has a larger area than the LGA 1972 “county” of “Lancashire” !

Clearly each of the three types of “county” has its own role to play in contemporary society and a solution has to be found to this “county confusion”. Such a solution requires three things:

- that the nature of each of the three types of “county” be clearly understood;

- that a common terminology be generally adopted to differentiate between the three types of “county”;

- that a single set of these “counties” be adopted as the basis for a standard general-purpose geographical reference frame for Britain.

This document aims to provide these three things. In Section 2 we explain the nature of the three types of “county” and how they relate to each other. In Section 3 we propose that the following set of terminology be generally adopted to differentiate between them:

(i) the historic counties be referred to as either the “historic counties” or, simply, “the Counties”.

(ii) the LGA 1972’s “counties” be referred to as either “administrative counties” or “unitary authority areas” depending on whether they have a two tier or single tier local government structure.

(iii) the LA 1997’s “counties” be referred to as the “ceremonial counties” or “lieutenancy areas”.

Finally, in section 4, we point out that administrative areas are unsuitable as a basis for popular geography since their names and areas are subject to frequent change. Instead, we propose a general return to the use of the historic counties for this purpose. We also propose that “county confusion” could be further reduced by legislation which:

(i) ties the areas of the “ceremonial counties” to those of the historic counties.

(ii) re-labels the local government areas of the LGA 1972 as either “administrative counties” (for areas with an existing “county council” and several “district councils”) or “unitary districts” (for areas where a single council administers all local government functions).

2. A guide to the three types of “county”

2.1 The historic counties

The division of England into shires, later known as counties, began in the Kingdom of Wessex in the mid-Saxon period, many of the Wessex shires representing previously independent kingdoms. With the Wessex conquest of Mercia in the 9th and 10th centuries, the system was extended to central England. At the time of the Domesday book, northern England comprised Cheshire and Yorkshire (with the north-east being unrecorded). The remaining counties of the north (Westmorland, Lancashire, Cumberland, Northumberland, Durham) were established in the 12th century. Rutland was first recorded as a county in 1159.

The Scottish counties have their origins in the ‘sheriffdoms’ first created in the reign of Alexander I (1107-24) and extended by David I (1124-53). The sheriff, operating from a royal castle, was the strong hand of the king in his sheriffdom with all embracing duties – judicial, military, financial and administrative. Sheriffdoms had been established over most of southern and eastern Scotland by the mid 13th century. Although there was a degree of fluidity in the areas of these early sheriffdoms, the pattern of sheriffdoms that existed in the late medieval period is believed to be very close to that existing in the mid-nineteenth century. The central and western Highlands and the Isles were not assigned to shires until the early modern period, Caithness becoming a sheriffdom in 1503 and Orkney in 1540.

The present day pattern of the historic counties of Wales was established by the Laws in Wales Act 1535. This Act abolished the powers of the lordships of the March and established Denbighshire, Montgomeryshire, Radnorshire, Brecknockshire and Monmouthshire from the areas of the former lordships. The other eight counties had, by then, already been in existence since at least the 13th century. The historic counties are, however, based on much older traditional areas.

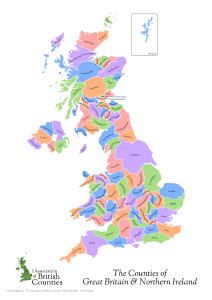

The  ABC map of the historic counties of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

ABC map of the historic counties of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

While each County may have originally been set up for some public purpose or other, long before the beginning of the nineteenth century it was their geographical identity that was paramount. No single administrative function defined them. Rather, the Counties were considered to be territorial divisions of the Country whose names and areas had been fixed for many centuries and were universally known and accepted. The Counties were clearly recognised legal entities. This is witnessed by the fact that innumerable Acts of Parliament made reference to them and used them as the basic geographical framework for various administrative functions.

An illustrative example of the way in which Parliament used the Counties is provided by the Militia Act 1802 (c.90 42 Geo III). This Act described the areas within which the militia were to be organised and, in particular, within which there was to be a lord-lieutenant. It ascribed a lord-lieutenant to each of the Counties (and one each to the three ridings of Yorkshire). The Act made no attempt to qualify or define what it meant by the word “County”. It did not need to. The names and areas of the Counties were universally known and accepted and had been so for centuries. However, what the Militia Act (1802) did do was to describe exceptions to the basic County geography for the organisation of the militia. For example, the Governor of the Isle of Wight was to be the lord-lieutenant of the island; the Warden of the Cinque Ports was to be lord-lieutenant of the Cinque Ports.

Other Acts used the Counties as a starting point to define areas for other types of administration (e.g sheriffs and Members of Parliament). Again these Acts did not need to define what the Counties were or to detail their bounds. They also, however, explicitly listed those slight exceptions to the framework of the Counties which were considered necessary from the standpoint of administrative expediency. Hence the areas of the jurisdiction of lord-lieutenants and sheriffs could differ slightly (due for example to a different way of dealing with a particular detached part) without it actually affecting the general understanding of what the Counties were. This is a major difference between the Counties and those areas deemed to be “counties” within LGA 1972 or LA 1997. These modern Acts explicitly define their own areas and then give them the label “county”. Up until 1888, Acts used the pre-existing Counties.

The era of modern local government began with the Local Government Act 1888 (LGA 1888). The LGA 1888 created a whole new set of statutorily defined administrative areas covering the whole of England and Wales, terming them “administrative counties” (two-tier local government areas) and “county boroughs” (single-tier local government areas). The Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889 created similar administrative areas in Scotland.

Initially the combined area of an “administrative county” with its “associated county boroughs” was similar to that of the historic county from which the “administrative county” took its name (e.g. in Warwickshire, the combined area of the “administrative county of Warwick” with the “county boroughs” of “Birmingham” and “Coventry” was very similar to that of the historic county of Warwick). However, subsequent changes to local government areas took place leading to small divergences in area between the Counties and their “administrative county” namesakes.

However, the LGA 1888 did not abolish or alter the historic counties. This fact is evident from the General Register Office’s Census Report of 1891. This distinguished between what it called the “Ancient or Geographical Counties” and the new “administrative counties”. It made it clear that the two were distinct entities and that the former still existed. It provided detailed population statistics for both sets in its 1891, 1901 and 1911 reports.

No subsequent Act has ever tried to alter or abolish the historic counties and their continued existence has been reaffirmed consistently by the Government (e.g. the quote in Section 1). However, what is true is that they are no longer used as the basis for any major form of public administration. Prior to 1888 the areas of the sheriffs and lord-lieutenants were based upon the historic counties. The LGA 1888 tied them to the new “administrative counties”. In 1917 parliamentary constituencies were also redrawn and based on the “administrative counties”. This was the end of the last major administrative use to which the Counties were put. The General Register Office then stopped producing detailed statistics for the Counties. However, until 1971 it continued to refer to them in its County Reports drawing a clear distinction between them and the “administrative counties” and “county boroughs”.

Whilst the Counties are no longer used directly as the basis for any major form of public administration they do, of course, remain significant cultural and geographical entities. In relation to the English counties this was re-affirmed on 12 April 2013 by Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Eric Pickles:

“Today, on St George’s Day, we commemorate our patron saint and formally acknowledge the continuing role of our traditional counties in England’s public and cultural life.”

2.2 The “counties” of the Local Government Act 1972

The LGA 1972 explicitly abolished all of the “administrative counties” and “county boroughs” created by the LGA 1888 and created a whole new set of local government areas. To quote from the LGA 1972:

“1 (1) For the administration of local government on and after 1st April 1974 England (exclusive of Greater London and the Isles of Scilly) shall be divided into local government areas to be known as counties and in those counties there shall be local government areas to be known as districts.”

This unqualified use of the word “counties” by the LGA 1972 has been the source of great confusion. However, it is clear from this extract that these “counties” are nothing more nor less than “local government areas” which are “to be known as counties” and which exist “for the administration of local government”. The word “county” is a label within the terminology of the Act to refer to these top-tier local government areas defined by it. Such a definition of a word within an Act for a particular purpose should not be taken to have any bearing upon the ordinary, popular meaning of that word. Rather it is an admission that, within that Act, the word is not being used in its ordinary, popular sense.

Whilst the LGA 1972 explicitly abolished all the “administrative counties”, it said nothing about the Counties themselves. The Government was and is happy to confirm that this was because these were unaffected by the Act.

Whilst the “administrative counties” of the LGA 1888 had been closely based upon the historic counties, the LGA 1972’s “counties” were, in many areas, radically different. For example, Section 1(2) of the LGA 1972 subdivides the “counties” of this Act into “metropolitan counties” and “non-metropolitan counties”. The “metropolitan counties” (i.e. “Greater Manchester”, “West Midlands”, “West Yorkshire”, “South Yorkshire”, “Tyne and Wear” and “Merseyside”) bear no relation to any historic county. Many of the “non-metropolitan counties” created by the Act as originally passed were also not based on any historic county (e.g. “Cumbria”, “Avon”, “Clwyd”, “Humberside” etc.). Others bore the name of a historic county despite having a radically different (usually much smaller) area (e.g. “Somerset”, “Lincolnshire” etc.).

The LGA 1972, as passed, bestowed councils (“county councils”) on each “county” created. The system of local government it created has since been radically altered in many areas. Firstly, the county councils for the “metropolitan counties” were abolished by the Local Government Act 1985 although the “metropolitan counties” themselves were not abolished. Secondly, the Local Government Act 1992 created a mechanism for the revision of the local government structure in England. A Local Government Commission made recommendations to the Secretary of State who then enacted those with which he agreed via Statutory Instruments. The main result of this process was the creation within England of 46 local government areas which had only one council with responsibility for all the functions shared between the “county council” and the “district councils” in other areas. There are three different ways in which this was done:

(i) There are 39 “counties” created which have only a single district which has the same name and area as the “county”. In these cases there is a “district council” but no “county council”. For example whilst there is now a “county” called “Stockton-on-Tees” this “county” has no council. However, within this “county” is one district (also called “Stockton-on-Tees”) which has a council, “Stockton-on-Tees District Council”.

(ii) The LGA 1972 “county” of Berkshire still exists but it has no “county council”. All administrative functions have been devolved to the 6 “district councils” (i.e. “Reading”, “Slough”, “West Berkshire”, “Windsor and Maidenhead”, “Wokingham”, “Bracknell Forest”).

(iii) The LGA 1972 “county” of the “Isle of Wight” has no “district councils”. The sole council (known as the “Island Council”) is the “county council”.

A further round of reforms from 2008-2010 created 5 more unitary authorities. These were created by abolishing the district councils in the “counties” of “Northumberland”, “Wiltshire”, “Shropshire”, “Cornwall” and “County Durham” leaving the county council the unitary council. “Dorset” and “Buckinghamshire” suffered this fate too in 2019-2020.

The structure of local government within “Greater London” is still principally governed by the London Government Act 1963. This Act abolished the “administrative county” of “Middlesex” and altered the areas of the “administrative counties” of “Surrey”, “Essex” and “Kent” (but did not alter the areas of the historic counties of these names). The Act created the “London boroughs” and their councils. It left the Corporation of the City of London in charge of administration within the City. The status of the “Inns of Court” (i.e. the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple) was also unaffected by the Act. Each of these continues to be administered by a “Master of the Bench”. The Act also created “Greater London” itself, defining it to be the sum of the areas of the “London boroughs”, the City of London and the Inner and Middle Temples. Note that whilst “Greater London” is a “local government area” it is not a “county” within the meaning of the LGA 1972. The Act as passed also created the “Greater London Council” (GLC). The GLC was abolished by the Local Government Act 1985, but “Greater London” itself was not abolished. The Greater London Authority Act 1999 created the “Greater London Authority”. However, the GLA is better considered to be a regional assembly rather than a local authority.

With regard to Wales, the LGA 1972, as originally passed, had created a local government structure similar to that in England with eight “counties”. The Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 (LG(W)A 1994) reorganised local government in Wales by amending the LGA 1972. There are now 22 single-tier local government areas described by Section 20(1) of the amended LGA 1972 as the “new principal areas”. However, Section 20(4) of the LGA 1972 then describes 11 of these as “counties” and 11 as “county boroughs” (despite all 22 areas being identical in every other respect of the Act!). Of the 11 “counties”, four are very close in area to a historic county and borrow its name. However, three (“Flintshire”, “Denbighshire” and “Monmouthshire”) borrow the name of a historic county despite having a radically different area to the County of that name.

Local government in Scotland is now provided by 30 “local government areas” (under the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994). Whilst this Act wisely does not label these local government areas as “counties”, many of them do, nonetheless, bear the name of a historic county despite having an area very different from that County (e.g. “Aberdeenshire”, “Renfrewshire”).

The net result is that, in local government terms, Britain can be considered to be split into 24 LGA 1972 “counties” where service  provision is split between a “county council” and several “district councils” (we suggest the label “administrative county” be adopted for these areas – see Section 3 below) and 182 areas where service provision is the responsibility of a single local authority (we suggest the label “unitary authority area” be adopted for these areas – see Section 3 below).

provision is split between a “county council” and several “district councils” (we suggest the label “administrative county” be adopted for these areas – see Section 3 below) and 182 areas where service provision is the responsibility of a single local authority (we suggest the label “unitary authority area” be adopted for these areas – see Section 3 below).

The Local Government Map shows the distribution of these “administrative counties” and “unitary authority areas”. Note that, in terms of legislation, there are ten distinct types of local government area which fall under the “unitary authority area” label. The map and the accompanying keys show the breakdown of the “unitary authority areas” into these ten categories. A key to the Local Government Map and further details can be found on the Gazetteer of British Place Names website.

2.3 The “counties” of the Lieutenancies Act 1997

This act provides for the appointment of the lord-lieutenants in Great Britain and contains various provisions relating to their operation. To quote from it:

“1.-(1) A lord-lieutenant shall be appointed by Her Majesty for each county in England, each county in Wales and each area in Scotland (other than the cities of Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow).

(4) Schedule 1 to this Act (which identifies the areas which are counties in England and Wales and areas in Scotland for the purposes of the lieutenancies) shall have effect; and in this Act “county” and “area” shall be construed accordingly.”

With regard to England these “counties” are defined in terms of the local government areas of the LGA 1972. For example, the start of the Table in Schedule 1 reads:

County for the purposes of this Act Local government areas Bedfordshire Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Luton Buckinghamshire Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes Derbyshire Derbyshire and Derby

Many of the “counties” of the LA 1997 are actually combinations of “counties” of the LGA 1972. Under the LGA 1972 the local government areas of “Buckinghamshire”, “Derbyshire”, “Luton”, “Milton Keynes” and “Derby” are all counties (although the last three have no county council and only a single district).

In statutory terms there are therefore two areas which could claim to be “Buckinghamshire”: one as defined by the LA 1997 and including the LGA 1972 “county” of “Milton Keynes” and the other as defined by the LGA 1972 and excluding “Milton Keynes”. There are, in fact, 21 cases in England where a “county” within the meaning of the LA 1997 has the same name as a “county” within the meaning of the LGA 1972 but a different area.

The “counties” for the purposes of the LA 1997 are not exclusively combinations of local government areas. For example, the “county” of “Durham” (for the purposes of LA 1997) consists of the local government areas of “Durham, Darlington, Hartlepool and so much of Stockton-on-Tees as lies north of the line for the time being of the centre of the River Tees”. The rest of the local government area (and “county” in terms of the LGA 1972) lies in the LA 1997 “county” of “North Yorkshire”.

With regard to Wales, the “counties” of the LA 1997 are defined to be the “preserved counties” of the LGA 1972. These are the eight “counties” as defined by the LGA 1972 as first passed (e.g. “Clwyd”, “Dyfed” etc.) but slightly amended by the LG(W)A 1994 and further amended by the Preserved Counties (Amendment to Boundaries) (Wales) Order 2003.

With regard to Scotland, the LA 1997 says: “Her Majesty may by Order in Council divide Scotland (apart from the cities of Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow) into such areas for the purposes of this Act as she sees fit.” The present such order is “The Lord-Lieutenants (Scotland) Order 1996”. There are 33 such areas (excluding the four cities). Many of these “areas” bear the name of a historic county although few are closely coincident with that county.

3. A proposed terminology to clear the confusion

A first step in clearing up the current “county confusion” is the general adoption of a form of terminology which enables a clear distinction to be made between the 3 types of “county”. A.B.C. proposes that:

(i) the historic counties be referred to as either the “historic counties” or, simply, “the Counties”.

(ii) Those of the LGA 1972’s “counties” which still have an existing “county council” and several “district councils” be referred to as “administrative counties”. All other local government areas (in which a single council administers all local government functions) be referred to as “unitary authority areas”.

(iii) the LA 1997’s “counties” be referred to as the “ceremonial counties” or “lieutenancy areas”.

As noted in Section 2.1, the phrase “Ancient or Geographical Counties” is the preferred “official” term to refer to the historic counties. It was coined by the General Register Office in 1891 and used in Census Reports and by the Ordnance Survey from that date. However, it might be felt too lengthy and cumbersome for popular use. Instead we suggest that the phrase “historic counties” has much to recommend it. This is the phrase used by the Encyclopaedia Britannica to refer to the Counties and is also apparently that preferred by the UK Government. Since these Counties are the original Counties the unqualified term “Counties” should also be understood to refer to these areas.

The phrase “unitary authority” has now become a standard term (e.g. by Ordnance Survey, the Office for National Statistics, Royal Mail) to describe those local government areas which have only a single local authority. However this is not a statutory phrase within any local government legislation. Rather it is a popular term used to cover a variety of different types of local government areas created by different Acts. The discussion in Section 2.2 and the Local Government Map makes clear the variety of types of area which could reasonably be considered to fall in this category.

In ABC’s view the phrase “unitary authority” has much to recommend it since it makes clear the undivided nature of the councils’ powers. Our only reservation would be that it is generally the local government areas which are being referred to by this expression and not the authorities themselves. Hence “unitary authority area” is a more apt expression.

Unfortunately, alongside the use of “unitary authority”, it is still common to see the use of the unqualified word “county”. It is currently used by Ordnance Survey to refer to those “counties” of the LGA 1972 which still have both “county councils” and “district councils”. However, within the meaning of LGA 1972, all but six of the “unitary authorities” of England are also “counties” and so are the “metropolitan counties”. It is confusing enough having three types of “county”. OS has created a new definition of “county” comprising a subset of the LGA 1972’s “counties”. This mix of a self-defined popular expression (“unitary authority”) with a redefinition of a statutory phrase (“county”) is highly confusing.

Instead, ABC suggests that those local government areas which still have a “county council” and “district councils” should be described by the expression “administrative county”. In local government terms, the whole of Britain could be described as being split into “unitary authority areas” (with single councils providing all services) or “administrative counties” (with extant councils at both top tier and lower tier levels). The phrase “administrative county” is well understood, has a long pedigree and is that used by the Encyclopaedia Britannica to refer to these areas. It is also that used by Royal Mail in its Alias File.

The phrase “ceremonial counties” is already commonly used to refer to the lieutenancy areas and seems appropriate. For example, the Ordnance Survey and the UK Government use this phrase to refer to these areas. Unfortunately, the Encyclopaedia Britannica refers to these areas as “geographic counties”. Whilst ABC agrees with Britannica’s use of the terms “historic county” and “administrative county”, the term “geographic county” is inappropriate for the lieutenancy areas for three reasons. Firstly, no-one in the UK refers to these areas using this term. Secondly, all of the various types of “county” are “geographic” areas. Thirdly, the term is too similar to “geographical county” which would usually be taken to mean “Ancient or Geographical County” (i.e. what Britannica calls “historic county”).

4. Concluding remarks – a fixed popular geography

Administrative geography is, of course, important in many contexts but administrative areas can never form a popular geographical framework because their names and areas are subject to frequent change. Many of the current set are unfamiliar to many people and are unlikely ever to become familiar. With the advent of the concept of “unitary authorities” there are also now 206 top tier local government areas in Britain (compared to 86 historic counties). Many of the local government areas are too small to be much use as a basis for popular geography. Also many of them borrow the name of a town or city within them. This renders them useless in a geographical context (e.g. “Q: Where is Caerphilly ?”, “A: In Caerphilly” !). The current set of ceremonial areas are such a bizarre mix of extinct and extant local government areas along with some total oddities (e.g. “Roxburgh, Ettrick and Lauderdale”) that they do not form any kind of publicly recognisable geographical framework.

ABC contends that the historic counties are the only Counties which can provide a popular geographical framework. The names and areas of the Counties are fixed and familiar to most people. They are still used in popular parlance (and also frequently by the media) as the basis for geographical descriptions. They are also still important cultural and social entities. The 6 Counties of Northern Ireland, like those of Britain, are no longer used for administrative purposes. Yet these Counties are still used as the standard geographical framework of Northern Ireland. There is no practical reason why the Counties of Britain should not be similarly used.

The general adoption of the historic counties of Britain as a popular geographical framework requires a change of convention rather than any legislation. Nonetheless, an end to the current chaos and the establishment of a fixed popular geography would certainly be aided by legislation which:

(i) ties the areas of the “ceremonial counties” to those of the historic counties.

(ii) re-labels as “administrative counties” those “counties” of the LGA 1972 within which there is an extant “county council” and several “district councils”.

(iii) abolishes those “counties” of the LGA 1972 in which only one tier has an extant “council” and, in their place, creates a set of “unitary districts”.

(iv) re-labels the “counties” and “county boroughs” of Wales and the “local government areas” of Scotland as “unitary districts”.

The offices of lord-lieutenant and sheriff were based on the Counties for many centuries. These are now distinct from local government areas. A return of these functions to the Counties seems appropriate in an administrative sense and would certainly help reduce “county confusion”.

The redefinition of the terminology of local government has the twin aims of making local government terminology consistent with itself and of drawing a clear distinction between local government areas and the Counties. A quick perusal of the Local Government Map makes clear that the absurd mess that local government terminology is currently in needs to be sorted out urgently.