County Durham Day is celebrated each 20th March, the date of Saint Cuthbert’s death. In anticipation of the big day, we present our Portrait of County Durham.

County Durham is a maritime county in the north-east of England. Known as “the Land of the Prince Bishops”, the county was a county palatine under the rule of the Bishop of Durham from the Middle Ages until 1836.

Durham’s history was forged by the troubles of the Middle Ages. The Industrial Revolution prompted exploitation of its extensive coalfield, dramatically changing its character. New mining villages were built. Its towns developed as centres of heavy industry, particularly iron and steel production and shipbuilding. The decline of these industries has seen the character of the county change again, with the establishment of new towns, industrial and business parks, and a move towards light industry, technology, services and tourism.

The Durham Dales occupy the west of the county, a landscape of high exposed moorlands, hills and mountains. The River Tees rises in Cumberland before forming County Durham’s border with Westmorland and then its long border with Yorkshire. County Durham’s border with Cumberland runs across the peaks to where County Durham, Cumberland and Northumberland meet by Killhope Head. From here County Durham’s border with Northumberland crosses the fells and thence along the River Derwent. Consett is perched on the steep eastern bank of the Derwent, on the edge of the Durham Dales.

At Wearhead, the River Wear starts its long, meandering journey through some of the county’s best known towns and countryside. Upper Weardale is famed for its beauty, surrounded by high fells climbing up to 2,447 feet at Burnhope Seat (eastern summit), the county top, with heather grouse moors. The dale’s principal villages include St John’s Chapel, Stanhope and Wolsingham.

Upper Teesdale is a landscape of unrivalled drama. At High Force, the Tees plunges 70 feet over a rock precipice in one of Britain’s greatest waterfalls. Middleton-in-Teesdale lies a little downstream, amongst the hills. Barnard Castle, famous for its Norman castle, lies on the edge of the Durham Dales. The Bowes Museum has a nationally renowned art collection housed in a 19th-century French-style chateau. The 14th-century Raby Castle, near Staindrop, is famed for both its size and its art.

East from Staindrop, the south of the county lies within the Tees Lowlands, a broad, open plain dominated by the meandering River Tees and its tributaries. The whole area is gently undulating with wide views to the distant hills. Much of it remains a rural landscape of scattered small villages and farmsteads. Unspoilt villages, including Gainford, Carlbury, High Coniscliffe, Hurworth-on-Tees, Neasham and Middleton-one-Row, lie along the Tees.

Much of the Tees Lowlands is heavily urbanised. Newton Aycliffe was founded in 1947, one of the first of the post-war new towns. Darlington’s development owes much to the local Quaker families of the Georgian and Victorian eras, who were instrumental in creating the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the world’s first permanent passenger railway. Stockton-on-Tees, at the other end of the railway, grew on ship building, steel and chemicals. Billingham was founded circa 650 by a group of Angles known as Billa’s people. The chemical industry played an important role in the growth of Billingham.

Hartlepool, a port town on the North Sea coast, was founded in the 7th century around Hartlepool Abbey. In the Middle Ages it served as the official port of the County Palatine of Durham. The port grew with the development of the Durham coalfield. A portion of the docklands has been converted into Hartlepool Marina.

To the north of the Tees Lowlands is the East Durham Plateau, a low upland plateau of Magnesian Limestone falling eastwards to the sea and defined in the west by a prominent escarpment, from which there are panoramic views across the Wear lowlands to the Pennines. The heavy clay soils of the plateau support mixed, predominantly arable, farmland in an open rolling landscape of low hedges with few trees. The landscape has been heavily influenced by mining, quarrying and industry, its scattered mining towns and villages and busy roads giving it a semi-rural character in places.

The coast between Sunderland and Hartlepool used to be called the “black coast” following decades of coal waste being dumped directly onto the beach. Following a lengthy clean-up operation the coast has been reborn as the Durham Heritage Coast. The magnesian limestone that underlies this area has given rise to a spectacular landscape of cream-coloured cliffs intersected by denes.

Houghton-le-Spring and Hetton-le-Hole are large towns with long histories but which grew around the mining industry in the 19th century. Peterlee was a new town founded in 1948 and named after the celebrated Durham miners’ leader Peter Lee. Seaham is a seaside town based around its harbour, constructed in 1828. At Seaham Hall, in 1815, Lord Byron married Anne Isabella Milbanke. Their short-lived union produced the mathematician Ada Lovelace.

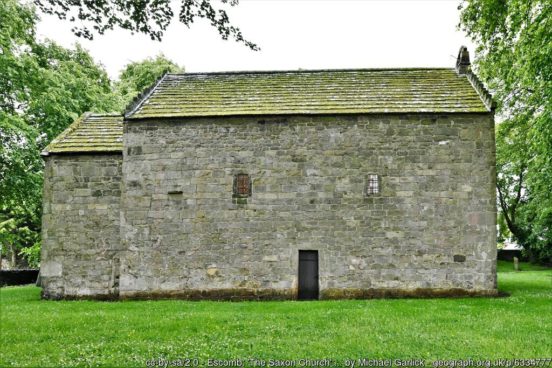

Between the Durham Dales and the East Durham Plateau are the lowlands of the Wear Valley. The former mining town of Crook lies just north of the Wear at the edge of the Dales. Bishop Auckland lies on the Wear a few miles further south. Much of the town’s early history was shaped by the Bishops of Durham who established a hunting lodge which later became their main residence, the splendid Auckland Castle. The route of the Roman road Dere Street passes through the town on its way to the Roman Fort at Binchester. The nearby village of Escomb has an Anglo-Saxon church built between 670 and 690.

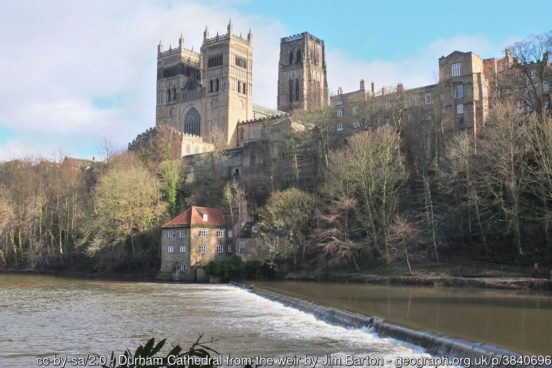

The City of Durham rises magnificently on a hill surrounded by the River Wear, crowned by its huge Norman Cathedral. Behind the cathedral is a precipitous drop down to the river. This site was chosen in troubled times as a defensible spot by the guardians of the bones of Saint Cuthbert, which now lie within the Cathedral. Their settlement here was the effective foundation of Durham and its status. The cathedral, along with the nearby Durham Castle, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The remains of Finchale Priory, a 13th-century Benedictine priory, are sited by the Wear four miles from Durham.

The Wear flows north to the ancient town of Chester-le-Street. Here the Roman’s built the fort of Concangis. This Roman fort is the “Chester” of the town’s name; the “Street” refers to the paved Roman road that ran through the town. The parish church of St Mary and St Cuthbert is where the body of St Cuthbert remained for 112 years before being transferred to Durham Cathedral, and the site of the first translation of the Gospels into English.

Washington was designated a new town in 1964, though based around and retaining the older village of Washington. Washington Old Hall (NT) is an early-17th-century manor house, with a 13th-century Great Hall. The manor was the ancestral home of the family of George Washington.

At the mouth of the Wear lies the city of Sunderland. Sunderland began as a fishing settlement before being granted a charter in 1179. Sunderland grew as a port, trading coal and salt. Ships began to be built on the river in the 14th century. By the 19th century, the port of Sunderland had absorbed Bishopwearmouth and Monkwearmouth. Since the decline of the city’s traditional industries, the area has become a commercial centre for the automotive industry, science and technology and the service sector. To the north of Sunderland are the resort town of Seaburn and the village of Whitburn, with its 18th-century windmill looking out to sea.

The north-east of County Durham is formed by the lowland plain south of the River Tyne and dominated by the towns which line the river’s southern bank. At the west of this stretch of the river are the former mining towns Ryton and Blaydon-on-Tyne. Whickham is a prosperous commuter town. Near to the former mining town of Stanley is the Causey Arch, the oldest surviving single-arch railway bridge in the world.

Gateshead lies on the Tyne, opposite Newcastle upon Tyne and joined to it by seven bridges, including the landmark Gateshead Millennium Bridge. The town’s economy is still based around the Team Valley trading estate, established in the 1930s. Gateshead is known for its iconic architecture such as The Sage Gateshead, the Angel of the North and the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

East of Gateshead lie Hebburn and Jarrow. Jarrow is world famous for its association with the Venerable Bede who lived, worked and died at St Paul’s monastery here. The monastery was founded by Benedict Biscop in 682 and a companion to the St Peter’s monastery he founded at Monkwearmouth in 674. The abbot Ceolfrith established the monastery as a centre of learning and scholarship. Bede composed the first book of English history; The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, creating the narrative which all future works were to follow. Both houses were sacked by Viking raiders, subsequently abandoned, but then refounded as cells of Durham Priory in the 14th century. Since the dissolution, the two abbey churches have formed the parish churches of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow. At Jarrow, substantial ruins survive next to St Paul’s church.

South Shields lies at the mouth of the Tyne, built on its docks and the industry that came with them. It remains one of the most important ports in the kingdom. The town’s North Sea coast has extensive beaches as well as the dramatic magnesian limestone cliffs of The Leas (NT). Marsden Bay, with its famous Marsden Rock, is home to a huge seabird colony. Souter Lighthouse (NT) (1871) was the first lighthouse in the world designed and built to be powered by electricity.

The lands of County Durham were part of the Kingdom of Northumbria from its foundation until the Viking incursions. In 866 Ivar the Boneless captured York and reduced the Northumbrian kingdom to just Durham and Northumberland. The lands that became County Durham were originally a liberty under the control of the Bishops of Durham, known variously as the “Liberty of Durham”, “Liberty of St Cuthbert’s Land” “The lands of St Cuthbert between Tyne and Tees” or “The Liberty of Haliwerfolc”. The bishops’ special jurisdiction was based on claims that King Ecgfrith of the Northumbrians had granted a substantial territory to St Cuthbert on his election to the see of Lindisfarne in 684. In about 883, a cathedral housing the saint’s remains was established at Chester-le-Street and Guthfrith, the Norse King of York, granted the community of St Cuthbert the area between the Tyne and the Wear. In 995 the see was moved again to the more defensive position of Durham.

In the 12th century a shire or county of Northumberland was formed. The crown still regarded Durham as falling within Northumberland until the late 13th century. In 1293 the bishop and his steward failed to attend proceedings of quo warranto held by the justices of Northumberland. The bishops’ case was heard in parliament, where he stated that Durham lay outside the bounds of any English shire and that “from time immemorial it had been widely known that the sheriff of Northumberland was not sheriff of Durham nor entered within that liberty as sheriff. . . nor made there proclamations or attachments”. By the 14th century Durham was accepted as a liberty which received royal mandates direct. In effect it was a private shire, with the bishop appointing his own sheriff. The area eventually became known as the “County Palatine of Durham”.

The County Durham flag was launched in 2013 and features the Cross of Cuthbert, counterchanged on the county colours of blue and gold. County Durham Day is celebrated on 20th March, the date of Saint Cuthbert’s death.

4 thoughts on “County Durham Day – 20th March”

Great article.

What a beautiful county yet scorned and mocked by Stockton on Tees that obsessively loves ‘Cleveland’ and all businesses and residents to a man woman or child write ‘Cleveland’ on their addresses and say that they are from ‘Cleveland’ despite that abolished post 1974 ‘county’ lasting until 1996.

Billingham exactly the same – always ‘Cleveland’ as for Stockton. The parts that ended up in Tyne & Wear well that’s done and dusted… such is the spell of that abomination (which is always written on addresses) that it manages to get people north of the Tyne to wilfully include the ‘enemy’ River of Wear in the tail end of their addresses, and correspondingly those south of the Tyne geographically around the Wear to love writing the word Tyne… at the start of their addresses!

I notice further afield that Cumbria as as expected will not ‘go away’ and is loved by those people in Lancashire North of The Sands, Westmorland, Cumberland and the bit of the old West Riding aka Sedbergh. So sad that Cumbria is ingrained and in the hearts and minds of all.

Avon seems to be sticking around forever particularly in Bath and Bristol.

The Royal Mail has bizarrely started to push ‘Greater Manchester’ on postal addresses yet stated it was never to be used at it’s inception in 1974, and the real counties were officially to be written. Now out of the blue it is appearing on Royal Mail Post Office websites and Post Office receipts.

Merseyside is here to stay, even those initially opposed in Southport and St. Helens have always willingly wrote it even though they wished to be known as being in Lancashire.

Powys continues unabated on addresses.

Highland and Borders are written 99% of the time to this day by people within those Scottish Regions but thankfully the rest of Scotland tends to stick to the real counties.

Good to see that Grimsby, Scunthorpe and south of the Humber write Lincolnshire (given that they were the most amenable to Humberside taking into account both sides of the said river).

West Midlands is a lost cause, with the whole Black Country across to Solihull declaring undying love for the fake county – even Coventry is starting to lean to WM where it was always identifying as Warwickshire – most interesting.

The London conurbation though has staunchly stuck to the traditional counties – one may have reasonably expected that region to have adopted

‘Greater London’.

One interesting and pleasing observation is that the County is very much in use in County town addresses with people for example writing Nottingham Notts., or Northampton Northants. even though county towns never need a county at the end!

Middlesbrough and the rest of the post 1974 ‘Cleveland’ keep that fake county as a Hill to Die on. There is absolutely nothing at all in Middlesbrough to link it to North Yorkshire – even the Boro’ fans (pre- Covid) sang something rude at Leeds United including ‘You dirty Yorkshire (so and so’s ….) fill in the blanks). Bizarre that a place utterly hates and despises it’s traditional county to a point of obsession – always ‘Teesside’ and ‘Cleveland’ in equal measure. Flying a North Riding flag in Middlesbrough would indicate to people it’s an Ireland flag (I’ve heard it on 2 occasions) and the White Rose flag is known for what it is and scorned and despised in ‘Boro.

So much for the Royal Mail changing the addresses back to the ceremonial counties – those ‘Teesside Clevelander’s’ hate Yorkshire off the scale – again so so sad as brainwashing there was all too easy!

Stockton and Billingham folk do indeed give the impression these days of being, on the whole, indifferent towards their historic county, sad to say. In Hartlepool, however, the situation may not be quite so hopeless, with the following Google results suggesting it’s a town that either is currently in the process of becoming reconnected to its Durham roots or simply never lost touch with them that severely in the first place:

“Marina Way Hartlepool Cleveland TS24” – about 1,170 results

“Marina Way Hartlepool County Durham TS24” – about 617 results

“Marina Way Hartlepool Teesside TS24” – 1 result

Can’t say I’m seeing much evidence of “Avon” persisting in the media or elsewhere outside of references to Avon and Somerset Police, though.

“Lansdown Road Bath Avon BA1” – about 986 results

“Lansdown Road Bath Somerset BA1” – about 6,880 results

An excellent portrait of my beloved county! Just a couple of typos to correct though: for ‘Causeway Arch’ read Causey Arch, and for ‘Should Shields’ read South Shields!

Thanks. Typos fixed now!