For the 50th anniversary of the local government re-organisation of 1st April 1974, we present a retrospective on the myth of the “changed” counties. We also call on the Government to finally resolve the ‘county confusion’ created in 1974, by establishing a set of local government terminology and local authority names which draws a clear distinction between local government and the historic counties.

1. Introduction

The Local Government Act 1972 radically reformed local government in England and Wales, creating a two-tier local government system of ‘counties’ and ‘districts’.

Many of the new ‘county councils’ were given the name of a historic county, despite having an area substantially different to that county, e.g. Lancashire County Council, Oxfordshire County Council, Cambridgeshire County Council etc.

The Government confirmed at the time that the 1974 re-organisation only affected the local government ‘administrative counties’ which had first been set up in 1889. It did not affect the ancient counties, most of which had been in existence for more than a thousand years and were always understood to be distinct entities to local government units.

Peter Boyce, Chairman of the Association of British Counties (ABC) said, “The historic counties are an important part of our history, geography and culture. Their identities have been seriously undermined by the ill-conceived way in which local government change in 1974 was handled.

It was a huge mistake to call local government areas ‘counties’ and to give any council an historic county name when it had an area radically different to that county.”

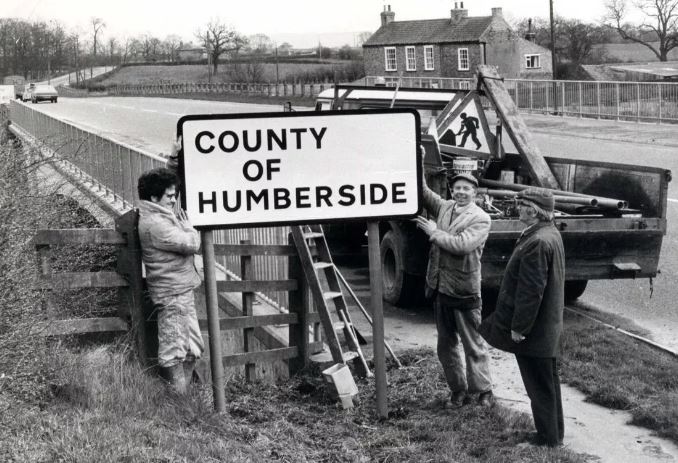

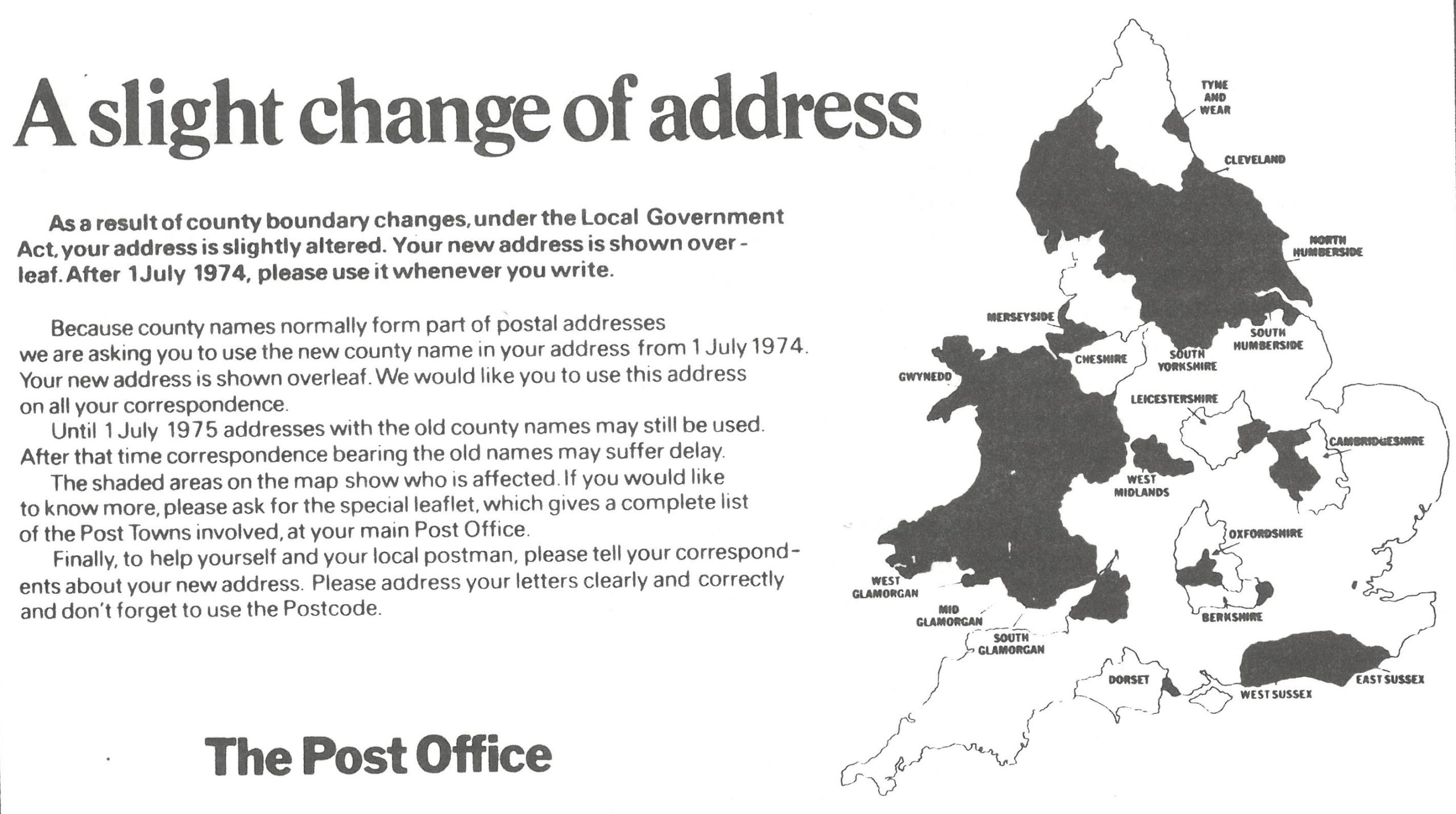

Despite the Government assurances that the counties were not affected by the 1974 local government changes, the Post Office, Ordnance Survey and the new councils acted as though they had been. Postal addresses, maps and road signage were changed to impose the new administrative geography for purposes it was never intended for.

Peter Boyce continued, “The geography of a thousand years was swept away and replaced by an administrative geography that lasted only 20 years before it started to fall apart. Confusion reigned.”

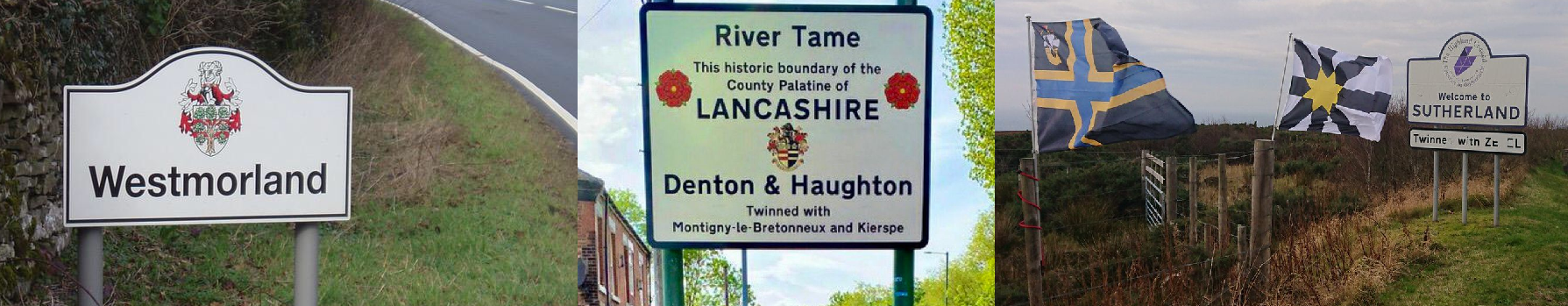

The 21st century has seen a renaissance of the historic counties, witnessed by the growth of county flags, county days, border signs, county groups and county-related social media. The Government published its own Celebrating the historic counties of England guidance. Despite this, the ‘county confusion’ begun in 1974 continues to challenge historic county identities.

Peter Boyce continued, “The Government’s support for the historic counties is very welcome. Nonetheless, it should back this up by rectifying the mistakes made in 1974. Local government needs a set of terminology and names which give it a totally separate identity to the historic counties.

The term ‘council area’ rather than ‘county’ should be used to refer to local government areas.

A council should only make unqualified use of a historic county name if it is close in area to that county. Names such as ‘North Northamptonshire Council’ are fine. Calling a council ‘Cambridgeshire County Council’ when it also covers most of Huntingdonshire is not.

Our nation needs a fixed general-purpose geography, a commonly accepted set of names and areas for people to use in all walks of life: travel, business, tourism, addressing, sport, hobbies, weather forecasts etc. The historic counties are the only credible choice for that.”

2. The Myth of the “Changed” Counties

Francis Hertzberg’s seminal book The Strange Case of the Counties That Didn’t Change was subtitled A Handbook to the Myth of the “Changed” Counties, the myth being that the local government changes of 1974 altered the counties of England and Wales.

When modern local government was first created in 1889, its areas were based on the ancient counties, but the local government entities created at that time were always understood to be distinct from the counties themselves. It was the 1889 local government areas and councils which were reformed in 1974, not the centuries-older historic counties. This fact is clearly expressed by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

At the time of the 1974 local government changes the Government itself said of the new local government areas: “They are administrative areas, and will not alter the traditional boundaries of counties, nor is it intended that the loyalties of people living within them will change.”

Despite this assurance, the Local Government Act 1972 did create a major challenge to the identities of the historic counties and their place in the national life since:

- It gave the unqualified label ‘county’ to the top-tier local government areas it created – from 1889-1974 these had been known as ‘administrative county’;

- It stated that the council of a top-tier area should be known as a ‘county council’;

- It tied the ceremonial offices of lord-lieutenant and sheriff to the new top-tier local government areas.

- It gave many of the new council areas the unqualified name of a historic county, even though the council area was radically different to that historic county. Those council areas known as Cambridgeshire, Essex, Hampshire, Kent, Lancashire, Lincolnshire, Oxfordshire, Somerset, Staffordshire, Surrey, and Warwickshire were especially egregious examples.

Although these changes only actually affected the local government areas first created in 1889, many believed that the counties themselves had been radically altered, that new counties had been created and that some counties had been abolished altogether.

The county confusion that resulted was compounded when the Post Office began insisting that the new council areas should form the postal county in many areas; when the new councils started putting up road signs for their areas and removing those showing the borders of the historic counties; and when the Ordnance Survey started marking the new council areas as ‘county’ on its maps, removing anything resembling the actual historic counties.

Peter Boyce, Chairman of the Association of British Counties, said, “The historic counties had formed the standard general-purpose geography of Great Britain for centuries, one rooted in history and commonly held notions of community and identity. In 1974, the powers that be decided to replace this with a new geography, one arbitrarily based on a set of local government areas defined at a point in time for a particular set of administrative purposes. History, identity, community and public understanding counted for nothing.“

In the years since 1974, the local government geography established then has been altered beyond recognition. Of the 54 top-tier county councils created in 1974, only 20 exist today and of those, only 9 cover their original area, the others having had large towns and cities removed and put into unitary authorities.

Peter Boyce continued, “The geography within which our history was played out was taken from us and replaced by an administrative geography that lasted only 20 years before it started to fall apart. The Office for National Statistics recommends the historic counties as a stable, unchanging geography which covers the whole of Great Britain. We wholeheartedly agree”

3. Charting a path away from county confusion

Fortunately, more than a thousand years of history and heritage doesn’t fade quietly away. What grew to become the traditional county movement began when the Yorkshire Ridings Society was founded in 1974. Many other county groups followed, leading eventually to the establishment of the Association of British Counties in 1989.

The local government geography of 1974 fell apart completely in the 1990s, with the gradual replacement of the two-tier local government system in many areas of England with unitary local government. All of the two-tier areas in Wales were replaced with unitary local government in 1996. Sadly, some of the post-1990 unitary authorities in England and Wales continue the pretence that they are counties e.g. Monmouthshire County Council, Denbighshire County Council, Durham County Council.

Local government in Scotland was completely reorganised in 1975 and then again in 1996. In one respect it now provides a model for what ABC would like to see in England and Wales, in that the word county appears nowhere in local government terminology, local government areas being known simply as council areas. Nonetheless, several of these council areas do grossly misuse an history county name, e.g. Aberdeenshire Council, West Dunbartonshire Council, Renfrewshire Council.

The break down of the 1974 local government geography did have the effect of making some in officialdom mend their ways. From 1996, the Post Office gave up trying to enforce the 1974 council areas within postal addresses. Since then, under its ‘flexible addressing’ policy, the historic county has been permissible in any UK postal address.

Reference works also began to realise that the paradigm of viewing the 1974 local government areas as literal replacements for the ancient counties was flawed. Encyclopaedia Britannica began using the phrase historic county to refer to the actual ancient counties and returned to using administrative county to refer to the local government ‘counties’. Britannica also began to treat the historic counties as extant entities of cultural and geographical importance. Given that since 1974 it had been describing them as ‘former counties’, this was a huge step forward.

Other reference sources followed suit. The understanding that a historic county is something separate from any kind of administrative area is now reflected in all credible reference sources, including the Office for National Statistics, the Ordnance Survey, the Gazetteer of British Place Names, Wikishire and Wikidata. The Historic Counties Standard provides the standard definition of the names, areas and borders of the historic counties.

4. A 21st-century renaissance of the counties

The progress made in the 1990s in clearing the confusion between the historic counties and local government paved the way for a 21st-century renaissance for the historic counties – seen in the growth of county flags, county days, county groups, county border signs and county-related social media.

Leading the charge has been the county flag phenomenon. In the early 1990s only a handful of counties had a recognised flag. At the latest count, fifty-six historic counties have a flag registered with the Flag Institute, including every English county. County flags have become familiar symbols: on flag poles, at sporting events, on marches, at festivals, on bumper stickers and on food packaging.

Jason Saber of British County Flags said, “The presence of county flags every year at Glastonbury, demonstrates their popularity. People are proud to show where they’re from and nothing is as immediately effective as a flag. County identities which may have once been overshadowed have been successfully reaffirmed through the adoption of a county flag. Huntingdonshire, Westmorland and Middlesex, for example, celebrate their county days with their flags proudly raised.”

Huge thanks are due to the Flag Institute for recognising that the notion of a county flag only made sense if it was a flag for a historic county, not for any kind of administrative area.

Starting with Yorkshire Day in 1975, the concept of a County Day on which to celebrate the history, heritage, culture and people of a county, has grown in popularity year on year. Around 25 historic counties now have a county day. Many are major events, on the ground and on social media. Yorkshire Day and Lancashire Day have a global reach.

Organisations and social media channels dedicated to celebrating a particular county now abound. Local authorities and the highways agencies have become increasingly open to erecting road signs marking the borders of historic counties.

Even the Government has begun to actively promote the historic counties, publishing its guidance to Celebrating the Historic Counties of England: “The historic counties are an important element of English traditions which support the identity and cultures of many of our local communities, giving people a sense of belonging, pride and community spirit. They continue to play an important part in the country’s sporting and cultural life as well as providing a reference point for local tourism and heritage. We should seek to strengthen the role that they can play.”

The Government has backed up these fine sentiments with deeds. It supports and promotes county days and every year for Historic County Flags Day (23rd July) it flies all the registered county flags in Parliament Square for the week, in a spectacular display.

5. Bringing an end to county confusion

Despite the many successes of the traditional county movement, much of the county confusion created by the Local Government Act 1972 persists. Here we highlight three local authorities that still make use of a historic county name despite having an area radically different to that county.

Philip Walsh, Chairman of the Friends of Real Lancashire said, “Lancashire County Council has an area that only covers about half of the historic county palatine. It does not cover the whole south of the real county including the famous Lancashire towns of Bolton, Liverpool, Manchester, Oldham, Rochdale, Salford, St Helens, Southport and Wigan. Neither does it cover the Lancashire North of the Sands area of the Lake District. It does cover the Forest of Bowland area of Yorkshire.

We have nothing against this local authority other than that it needs to choose a more appropriate name. Something like ‘Central Lancashire’ would at least end the confusion of this area with the real Lancashire.”

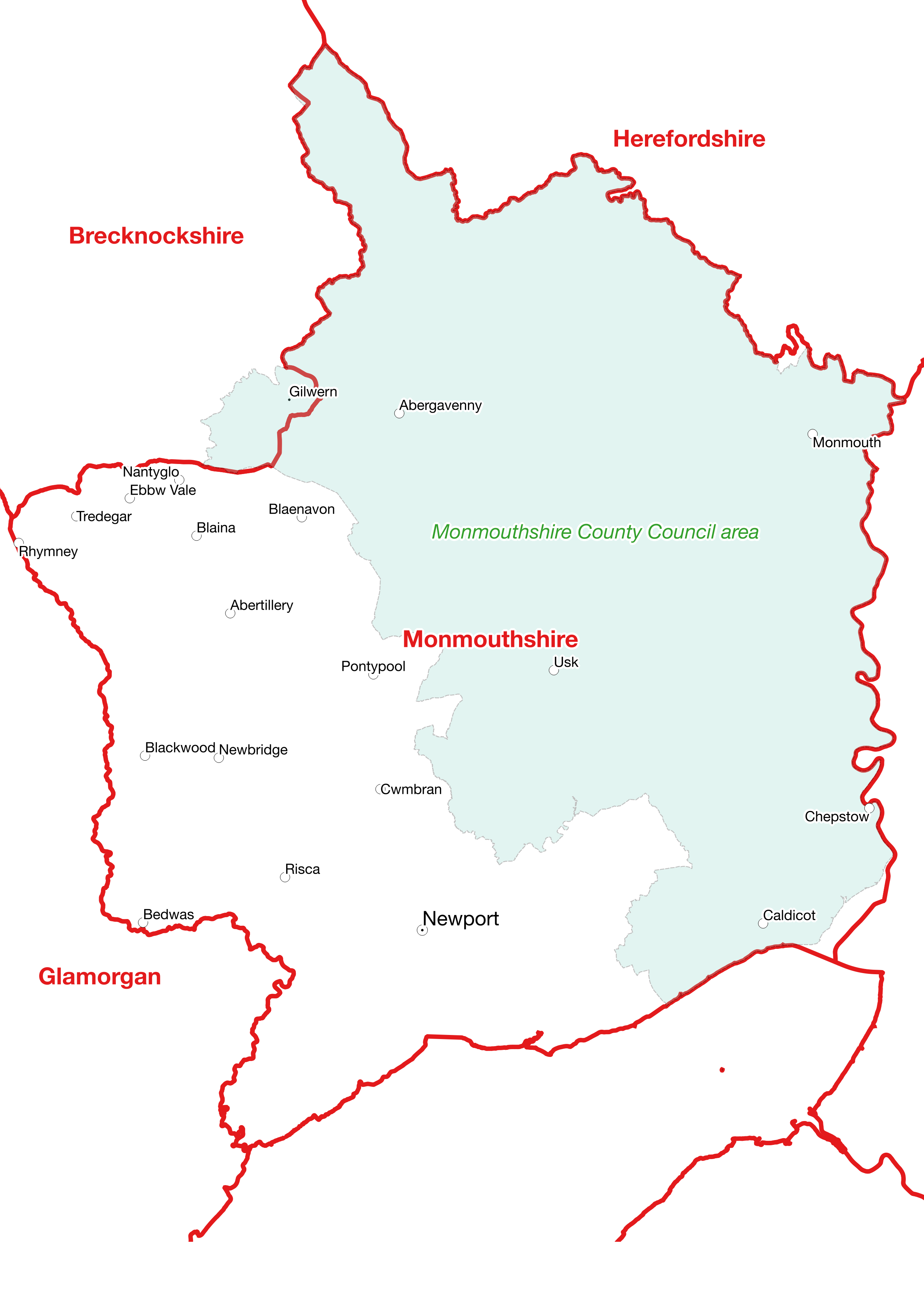

Owain Vaughan of the Monmouthshire Association said, “The identity of Monmouthshire has suffered badly from the ever-changing local government structures in its area and the wholly inappropriate names chosen for successive local authorities.

The original Monmouthshire County Council (1889-1974) covered an area close to the historic county. The 1972 Act then created a new local government ‘county’ labelled ‘Gwent’ with almost the same boundaries as Monmouthshire. This, coupled with the Act’s stipulation that ‘Gwent’ was to be considered part of Wales for local government purposes, had a profound effect on the identity of Monmouthshire. Gwent was abolished in 1996, but since then we have had a council which calls itself ‘Monmouthshire County Council’ but only covers the eastern half of the real Monmouthshire. This council should rename itself ‘East Monmouthshire Council’.”

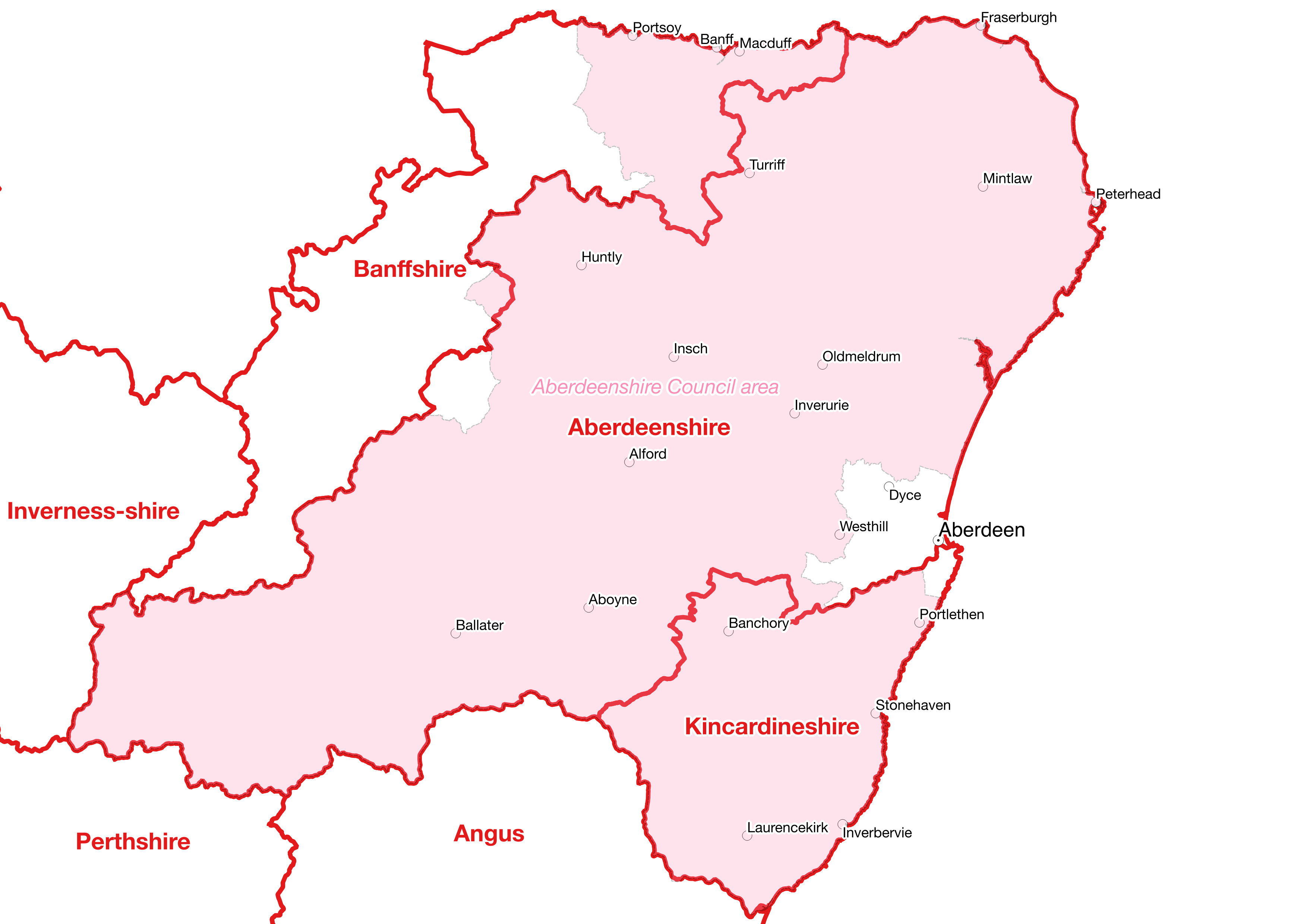

Neil Smith of the Kincardineshire Association said, “From 1975-1996, for local government purposes, Kincardineshire found itself within the Grampian region. This form of local government formed no threat to the identity of Kincardineshire as a county. However, from 1996, the county has been, for local government purposes, part of the Aberdeenshire Council administrative area. This has had a huge impact on our county’s identity, with many residents and visitors wrongly believing that the area is now part of Aberdeenshire.

The problem is the misuse of the historic county name of Aberdeenshire. If the 1996 council area had continued to be known as ‘Grampian’ then this confusion would not have occurred. We still have a lord-lieutenant of Kincardineshire but this seems to have little impact on the public perception of where we live.”

Peter Boyce, Chairman of ABC, added, “Although the office of lord-lieutenant has never defined the counties, most of which pre-date its creation by many centuries, in the past a lord-lieutenant was usually appointed to a historic county. Since 1974 most lord-lieutenants have been appointed to a local government area or the combination of local government areas.

A return to appointing the King’s representative to the historic counties could be seen as a recognition of the importance of both the counties and the lord-lieutenants. However, the experience of Kincardineshire shows that appointing a lord-lieutenant to a historic county is not enough in itself to maintain the county’s identity. Inappropriate local government names and terminology are the big threat to our historic counties.”

6. The future of the historic counties

Despite fifty years of county confusion, our historic counties remain a source of loyalty and identity to millions and the basis of innumerable sporting, social and cultural activities and organisations. They also still form the basis of geographical descriptions used millions of times every day. The Office for National Statistic recommends their use as fixed general-purpose geography for the whole of Great Britain.

ABC Chairman Peter Boyce said: “We know that millions of Britons love their county and we encourage them to promote and celebrate its history and heritage at every opportunity. Fortunately, there are many things local people, organisations, businesses and councils can do which have little or no cost.

Embrace your county’s flag. Fly it everywhere. Put a county flag sticker on your car’s bumper. Use it on your company’s signage and letterhead.

Join in the celebration of your county’s day. Set up a county day if one doesn’t exist. Festoon your workplace in county flags and bunting.

The most effective thing anyone can do to promote their county is also the easiest and cheapest – use your county in your address. It is especially effective for businesses to include their county in their address, particularly on shop signs, vans etc.

We are always on the look-out for new, imaginative, innovative ways of promoting and celebrating the historic counties. Things that will make the counties fun, relevant and important to future generations.”

Nonetheless, the problem of county-confusion needs to finally be resolved if the historic counties are to continue to play their important role in the national life for generations to come.

ABC Chairman Peter Boyce said: “Local government needs a set of terminology and names which give it a totally separate identity to the historic counties. The term ‘council area’, already used in Scotland, should be adopted throughout the UK. A council should only make unqualified use of a historic county name if it is close in area to that county. For general-purpose geography we need to return to the fixed framework of the historic counties.”

12 thoughts on “The Strange Case of the Counties That Didn’t Change”

Good article .

The BBC could help by not referring to bogus places as Tyne and Wear . North of the Tyne is Northumberland and south Durham .

Have you tried asking the BBC why they do this? Of all the meaningless local government area names, ‘Tyne and Wear’ is among the daftest. How can a place literally be in two rivers?! It’s also hard to imagine that anyone much, beyond the odd awkward beggar on social media, is going to object to the BBC referring to places as being in Northumberland or County Durham, both counties being perfectly familiar to people throughout the country.

Totally agree about the daftness of using ‘Tyne and Wear’ as a reference for general purpose geography. Retaining it as a ceremonial entity despite getting rid of the shrievalty and lieutenancy offices for nearby ‘Cleveland’ makes no sense whatsoever.

In my lifetime I want to see the ‘head of the dog’ county boundary shape of big Yorkshire reinstated in its true form pre-1974. That means properly reestablishing the Ridings made flesh, and all Yorkshire land then given to Lancashire, Greater Manchester, Cumbria and Durham acknowledged as being historically and technically in Yorkshire and relinquished back. Likewise any Yorkshire land taken from other counties returned to them, eg the Peak District area of Carl Wark, historically in Derbyshire). Although the Yorkshire overall historical boundary had been virtually unchanged from 1500s maps until the brainfart of the 1970s.

We lost a lot of Yorkshire land in the 1974 mess. Even if it was just ‘thought form’ land, its loss has been replicated again and again in modern documents, signage, internet sites, council literature and teaching, reinforcing the notion that admin trumps historic, so that now people living there and beyond believe admin boundaries are the only reality. In Yorkshire we ‘lost’ our large part of the Bowland Forest area, Mickle Fell/Lune Forest, our beloved Saddleworth and Dovedale Reservoir areas, Sedbergh, Dent and our part of the Howgills. We lost part of Whernside mountain, idiotically carved up between Yorkshire and Cumbria. And as reckless, if not more so, the historic county of Westmoreland, so loved by its people, lost its entire self. And part of Lancashire, a fascinatingly physically split county with many lovely gems, ended up in the administrative abomination that is Merseyside. Why have boring council politics been allowed to usurp the reality of historic borders?

So I’d like to see modern documents, websites, addresses, signage and all else rectifying the damage done to northern England’s regional identity. The morose, obtuse administrative boundaries have sadly been broadly adopted as if fact by people who accept the status quo, or fail to teach proper history and heritage, so that children are just replicating the complacency. This really needs correcting at government level.

So thanks for all the great work you do! I hope to see our marvellous British counties rightfully returned to their historical importance and detail across our island. It’s becoming so important in a world of increasingly fractured identity, in which our regional roots help to shape our national outlook.

While there’s no denying that northern England is the area of the country that’s been affected most by the 1974 carve-up, there are, nevertheless, several southern and midland counties that, in the forms they appear in on modern maps, are travesties of the real things. One of the worst examples is Berkshire, whose borders quite a few of its towns and perhaps as much as a third of its land are outside of according to most English ‘county’ maps produced nowadays.

Oh I agree, many travesties were carried out all around the country and the while thing is a farce that, to this day, leaves a catalogue of indignance, confusion or numb indifference/ignorance of history depending upon your view/stance. I particularly like to see Middlesex fight for its own identity amidst the quagmire of Greater London labelling, as Middlesex folk always seem pretty feisty.

Many thanks for your comments. We certainly have plenty of work to do to see our counties return to their former role as the standard general-purpose geography of the UK and continue to be an important part of the sense of community and identity. Nonetheless, as we tried to get across in the article, we have made a fair amount of progress and we’re certainly going to keep at it 🙂

To be honest,the damage has already been done.The 1972 Government act was an act of treason.Sadly as the older generation pass away the historic counties fade deeper into the long and distant past.

That’s too defeatist for me.

If you just roll over with no fight you might as well not bother breathing either imo. There’s always hope and with a fresh impetus to spread the word to younger generations and re-educate, partly via reinforcement and displaying local flags and correct historical boundaries on maps, wrongs can be righted.

We are only where we are now because of sheer complacency over time. The allowing of government to lead us. Not because any of that is accurate or truthful. Of course it’s worth fighting for. If you’re here and you believe in it, go out and fight for it as others do.

As an Australian of part-English descent, I fully agree with the aims and aspirations of the Association of British Counties. My car bumper bars are adorned with stickers of the four English counties from where my ancestors emigrated, viz. Devon, Somerset, Bedfordshire and Cumberland. It is encouraging to see that so many of the nonsensical changes of 1974 have disappeared and, like Mr Boyce and his friends, I am hopeful for the future.

the crazy name of Avon created in 1974 should of been better called Bristol as it was mostly that which was its administrive centre

Plus Somerset lost Weston Super Mare and Bath to Avon

I think it made Somerset suffer and it became a much poorer county than it was before 1974

Gloucestershire also got sucked up in its Southern end into Avon also

Now sensibly this part is called South Gloucestershire

Likewise after Avon was abolished the Southern half of Avon was returned to Somerset but not controlled by it and called North Somerset and Bath and North East Somerset but what a mouthfull of a name