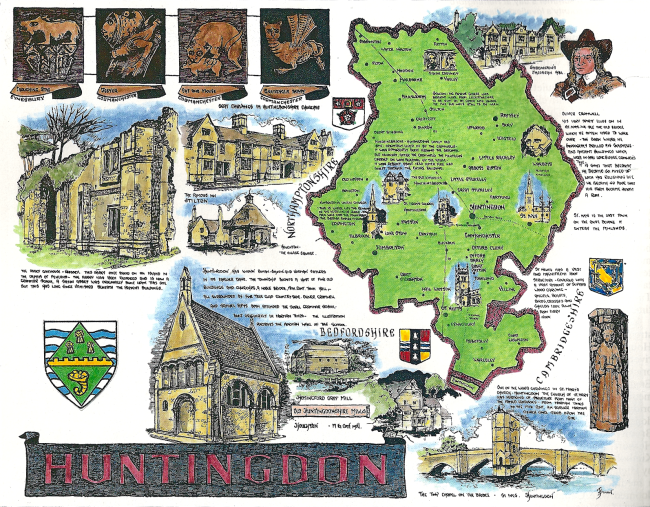

In this series of articles from the archives of This England, we step into Michael Bradford’s vision of Huntingdonshire from the summer of 1993. Local government reform is on the horizon and Huntingdonshire continues to fight for its identity. In 2014, as the prospect of a county flag for Cambridgeshire draws nearer, the two counties will have to reassert their own unique, but often entwined identities. Discuss Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire today in the Forums.

Huntingdonshire

‘A delightful spot that tends to lengthen life and make it happy’

Which of the ancient counties of England would win a contest for the most beautiful? Thomas Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby School, writing in 1833 from his beloved Fox How retreat in Westmorland, knew his holiday shire would come pretty near the top. Certainly he had some pretty harsh things to say about some of the others, including Warwickshire where his school was situated:

“I know of only five counties of England which cannot supply the longing for nature and I am unluckily perched down in one of them. These five are: Warwickshire, Northampton, Huntingdon, Cambridge and Bedford.”

Doubtless each of the five would put up plenty of champions against Arnold, but how, one wonders, did Huntingdonshire get on that list? It just shows how tastes differ and fashions change! Only 11 years before Arnold gave his verdict, William Cobbett, touring England on horseback, had gazed with rapture at the view from Huntingdon bridge:

“The most beautiful meadows that I ever saw in my life. It would be very difficult to find a more delightful spot than this in the world. It is one of those pretty, clean, unstenched, unconfined places that tend to lengthen life and make it happy.”

And long before that, in Queen Elizabeth I’s reign, William Camden had revelled in Huntingdonshire’s charms. The Upland part, he wrote, is “mighty pleasant, by reason of its swelling hills and shady groves”, while the entire scene, “as if contrived on purpose by some painter, perfectly charms the eye”.

This shy demure East Anglian shire has had a lot to put up with lately, especially the impact of modern transport and economic growth. You can still stand, like Cobbett, on the ancient bridge at Huntingdon taking in the lovely view to the east, but behind you rises a high-level modern road-bridge which not only crosses the Ouse but sweeps over the town as well, carrying noisy cars and roaring motorway juggernauts eastwards towards Felixstowe, Harwich and the sea. Huntingdon itself, once a sleepy market town, like St. Neots, the county’s second largest place, expanded swiftly to cope with new industries and prosperity in the 1970s and 80s, and the ancient centres of both are now surrounded with unlovely modern housing.

But there is still quietness and peace in the Shire, still the loveliness which eluded Thomas Arnold. Through the heart of it all glides the tranquil Great Ouse abounding with fish, lined with reed-beds and overhanging willows. In a broad, slow stream it passes some of the finest villages in England – Brampton, for instance, where the famous diarist Samuel Pepys had a farm and buried his money underground when a Dutch invasion was feared. It flows through Huntingdon, where England’s strong man, Oliver Cromwell, was born and, like Pepys, attended the Grammar School. Together with Godmanchester, its twin community, the county’s capital has lovely period houses dating back to Tudor, Stuart, Queen Anne and Georgian times.

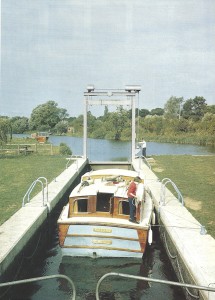

You can go from here by boat downstream past the 17th-century water-mill at Houghton, to Hemingford Grey, whose riverside church and thatched mellow brick cottages make it a match for any English village, and on to St. Ives, where a mediaeval chapel crowns the 15th-century bridge. Westward lie the rolling Huntingdonshire wolds, with villages like Leighton Bromswold whose vicar, the poet George Herbert, restored the fine church, and Kimbolton, red-roofed, with a broad sunny High Street, a 13th-century church and a mediaeval castle where Henry VIII’s doomed wife Catherine of Aragon spent her last four years.

History and nature blend easily in our small rural shires. North and east of Huntingdon is a land of vast horizons and huge skies, unmistakable marks of the endless Fens, drawing the eye towards the cathedrals at Ely and Peterborough. Here, before drainage took place in 1851, the county possessed the largest natural lake in southern England, Whittlesey Mere: now there are valuable nature reserves, Monks’ Wood, last nesting-place of the kite in England, and Holme Fen [1], abounding in marsh plants and wildfowl.

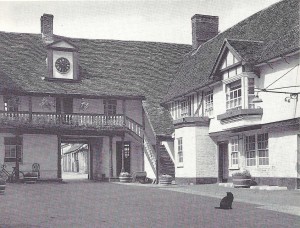

On the edge of the Fens an old Huntingdonshire coaching village has claimed for the Shire an honour which properly belongs elsewhere. Because Stilton lies on the old Great North Road, Leicestershire farmers used to bring their cheese here to The Bell, a still-surviving 17th-century coaching inn once frequented by Dick Turpin, for collection and transport to the capital. So far as Londoners were concerned the cheese was Stilton cheese because that’s where it came from.

It was the year 1965 that saw the beginning of the threats to Huntingdonshire (threats altogether greater than traffic pollution and tasteless building), for its status as one of the traditional English shires was put at risk by a political change – the Huntingdon and Peterborough Order – so that even its very existence seemed unsure.

To some at least that was how it appeared, though to others it was unthinkable. After all, Thomas Arnold and William Cobbett might have differed on the subject of the county’s attractions but there was one thing on which they would have agreed so readily that it would not have occurred to them to raise it.

They took Huntingdonshire as a place for granted. Like William Camden and Catherine of Aragon before them, like Cromwell and Pepys, like Dick Turpin, George Herbert and the poet William Cowper, who once lived in Huntingdon, they assumed that Huntingdonshire was there. True, no great natural features marked the county’s boundaries. In the west its landscape blends imperceptibly with Northamptonshire; to the east its flatness exactly matches that of Cambridgeshire. But the name and its associations went back hundreds of years, to William the Conqueror’s Doomsday Book and beyond, to the very beginning of counties. And its history and culture were Huntingdonshire’s alone, not Cambridgeshire’s or Northamptonshire’s.

For the previous 75 years the county had been administered by a county council but the Government of the day now decided that its population and rateable income were too small, inadequate to support the services which modern local government was expected to provide. And fortunately a “solution” was ready to hand, for another unit on Huntingdonshire’s northern border was also deemed too small – the so-called Soke of Peterborough, part of the historic County of Northamptonshire – so it was decided to unite the two of them under one council.

The rapidly-growing commercial and cathedral city of Peterborough was thus linked with the rural shire and was easily the largest place in the new area. This union recalled a much earlier formal link between the two places – a raised causeway through the swampy Fens constructed on the orders of King Canute 900 years before. The causeway had not threatened the identity of either. How would the new political link be seen? Could Hunts survive it?

The rapidly-growing commercial and cathedral city of Peterborough was thus linked with the rural shire and was easily the largest place in the new area. This union recalled a much earlier formal link between the two places – a raised causeway through the swampy Fens constructed on the orders of King Canute 900 years before. The causeway had not threatened the identity of either. How would the new political link be seen? Could Hunts survive it?

A lot depended on the new unit’s name, and fortunately the one chosen was the obvious one, “Huntingdon and Pteterborough” – obvious because “Huntingdonshire” alone would have been unfair to Peterborough, and vice versa. The double name had a double virtue, that of keeping Huntingdonshire alive – in tourism and postal addresses, for instance – and of recognizing the importance of a large, historic town whose roots were in another shire. On the whole, Huntingdonshire as a county-level place name survived 1965.

In the notorious administrative changes of 1974, however, the “big is beautiful” philosophy was taken a stage further. The reformers applied a still larger minimum population criterion to the shires and “Huntingdon and Peterborough” could not meet it even in combination. So they were united with Cambridgeshire in a new area to which the name of Cambridgeshire was given; and Huntingdon’s own name disappeared from the list of the administrative counties of England.

Other humiliations followed. The Shire lost its Lord Lieutenant and the Post Office casually deleted the name from its list of recommended postal addresses. If you write “Ramsey”, “St. Neots” or “Huntingdon” on envelopes nowadays you are supposed to put “Cambridgeshire” underneath. Many, however, refused to believe that they had moved house just because councils had changed and they persisted with “Huntingdonshire”.

“People outside the area,” wrote one ‘non-conformist’, “tell me I am living in the past and that there is no such place, but in the county there are many with deep and unwavering loyalty to Huntingdonshire.”

No such place indeed! But there was. Hadn’t the Government given repeated assurance that the changes were “only for local government” and “would not alter the traditional boundaries of counties”? And even in local government, the area of the old shire, unlike those of Westmorland and Cumberland for instance, had been retained – like a kind of pledge of happier days to come – but as a “district” not a “county”, and under the town-name of Huntingdon, not the Shire’s.

It was in May 1984 that the fightback began, for it was then that the loyalty felt by many individual people first found expression through their elected representatives. The local paper, which had never stopped calling itself The Hunts Post (“The county paper for Huntingdonshire”), reported that Huntingdon District Council had resolved to change its name to “Huntingdonshire”, and a band of morris-dancers from the Fens, founded to represent the old county and calling themselves “The Lost County Borders” group, danced in celebration. Boundary signs with the one word “Huntingdonshire” were erected (only to be taken down as recently as last summer on the orders of Cambridgeshire Council!). A Huntingdonshire Tourist Guide and a Huntingdonshire Accommodation Guide were produced, and the Shire’s towns and villages, which in 1974 had suffered the double indignity of losing Hunts and being made nominally subject to a mere town, Huntingdon, also rejoiced.

The District Council also heard from Huntingdon’s MP:

“I congratulate both the District Council and the Hunts Post for bringing this matter to the forefront of public attention. It seems to me that for the first time for many years a boundary or name change to the local community will actually enjoy the support of that community.”

It was an unmistakable dig at the perpetrators of “1974”.

Eight years later, last autumn, that same MP for Huntingdon, John Major, now Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spoke at his party’s annual conference about the current review of local government which would change the map yet again in two or three years time. He couldn’t be sure how it would go, he said, but again revealed his opinion of 1974 with the words: “Can you imagine Len Hutton walking out to bat for Humberside?”

The review operates under new rules and for Huntingdonshire it offers hope from two directions. No longer will the notion of a minimum size be used either to exclude the smaller areas from local government or to modify them for it. So there may well be a Huntingdonshire Council, and a top-level, unitary, all-purpose one at that; one that doesn’t have to kowtow to Cambridgeshire. But more fundamentally, the rules recognize the importance of ancient shires whether or not they have a council and will protect them by statute, where there is public demand, for maps, boundary signs, sport and so on.

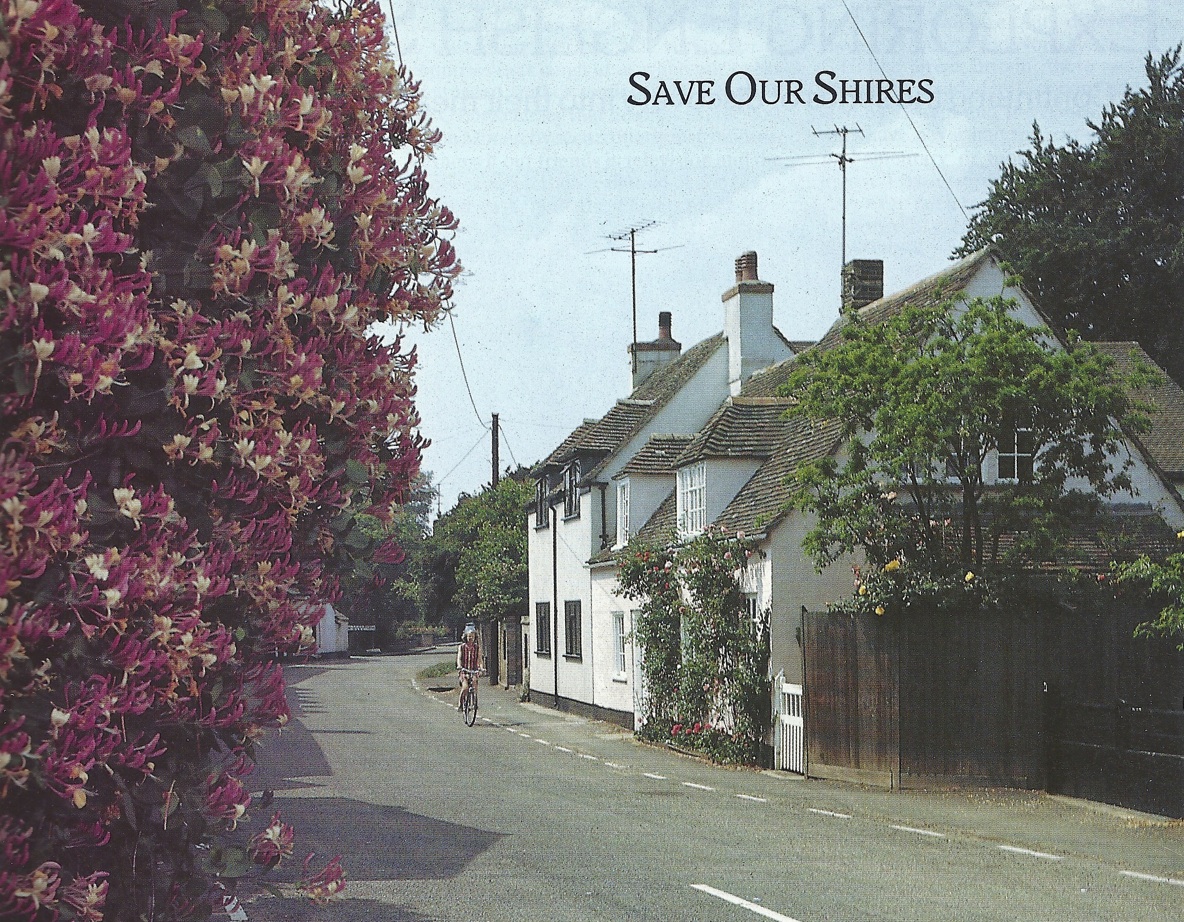

Indeed the language of politicians nowadays is the language of This England’s “Save our Shires” campaign:

“Old counties never die” cried the local government minister at that conference. “Nor do they fade away. The map of England is no blank page on which men in Whitehall can draw new lines. It is already criss-crossed by history, topography and geography. Somerset, Herefordshire, Rutland, the Ridings of Yorkshire, Huntingdonshire – if you want your past to become your future, say so and your wish call be granted.”

Whatever happens, Huntingdonshire exists, of course, but he was talking about public recognition. That being so, when the Local Government Commission comes round to Huntingdonshire later this year, will all the affection and loyalty that belong to a unique and ancient place find an adequate voice? We are sure that they will. MICHAEL BRADFORD

Notes:

1. Ed: the original article mentioned Wicken Fen, which is in Cambridgeshire.

From the Summer 1993 edition of This England.

Sales/Subscriptions:

This England, PO Box 326, Sittingbourne, Kent, ME9 8BR.

Telephone: +44 (0)1795 412823

E-mail: sales@thisengland.co.uk

www.thisengland.co.uk

Editorial:

This England, The Lypiatts, Lansdown Road, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, GL50 2JA.

Telephone: +44 (0)1795 412823

E-mail: editor@thisengland.co.uk

Have your say:

In 2014, as the prospect of a county flag for Cambridgeshire draws nearer, the two counties will have to reassert their own unique, but often entwined identities. Discuss Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire today in the Forums.